- Home

- Joscelyn Godwin

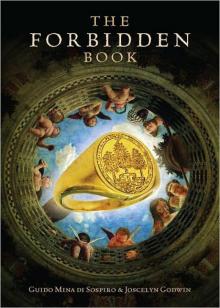

The Forbidden Book: A Novel

The Forbidden Book: A Novel Read online

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR THE FORBIDDEN BOOK

“This is a really excellent book—gripping, thought-provoking, mysterious, deep and resonant with esoteric knowledge. It keeps you turning the pages in a most compelling way. I couldn’t put it down.”

—Graham Hancock, author of the international bestsellers The Sign and the Seal, Fingerprints of the Gods and Heaven’s Mirror

“In the sure hands of Guido Mina di Sospiro and Joscelyn Godwin, The Forbidden Book is many things at once: murder mystery, meditation on religious extremism, and a complex but invitingly deep introduction into the esoteric. I don’t think I've encountered as original a book as this in a long time and I'm confident it will resonate with readers everywhere.”

—Mitchell Kaplan, co-founder of Miami Book Fair International, president of Books & Books, 2011 recipient of the Literarian Award for Outstanding Service to the American Literary Community by the National Book Foundation

“A harrowing tapestry of esoteric mystery, unseen history, and the search for inner knowledge—The Forbidden Book is the thinking-person's adventure yarn.”

—Mitch Horowitz, author of Occult America

“Watch out Dan Brown and Umberto Eco! Here’s a real esoteric thriller written by some real Illuminati who know the real thing and aren't afraid to let the secret out. Sex, magic, politics, and mystery. The Forbidden Book is a gripping, exciting, and illuminating read.”

—Gary Lachman, author of A Dark Muse: A History of the Occult, Jung The Mystic: The Esoteric Dimensions of Carl Jung’s Life and Teachings and The Quest For Hermes Trismegistus From Ancient Egypt to the Modern World

“Much more than simply a captivating adventure with a generous dose of love, intrigue, sex, and violence, The Forbidden Book provides an introduction to alchemical-magical practices of the late Italian Renaissance, a spiritual tradition that persists surreptitiously to this day. The authors, in possession of a deep understanding of—and sympathy for—esoteric Hermeticism, successfully weave pearls of occult wisdom into the fabric of their book, creating a compelling story-within-the-story that is all the more genuine for being based on an authentic early seventeenth century alchemical text. This is a book rich on many levels, with multiple layers of meaning and interpretation, from the riveting action-packed twenty-first century fictional narrative to deep insights into the ancient and enduring perennial philosophy. Indeed, The Forbidden Book is itself a modern incarnation of the ‘forbidden book’ which forms the central theme of the novel. Read it closely!”

—Robert M. Schoch, author of Voyages of the Pyramid Builders, Pyramid Quest and The Parapsychology Revolution

Copyright © 2012 Guido Mina di Sospiro and Joscelyn Godwin

Published by:

The Disinformation Company Ltd.

111 East 14th Street, Suite 108

New York, NY 10003

Tel.: +1.212.691.1605

www.disinfo.com

[email protected]

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a database or other retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means now existing or later discovered, including without limitation mechanical, electronic, photographic or otherwise, without the express prior written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012934722

eISBN: 978-1-934708-83-5

Cover design by Greg Stadnyk

Printed in USA

Disinformation® is a registered trademark of The Disinformation Company Ltd.

To Stenie and Janet, our beloved wives.

G.M.d.S. and J.G.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Afterword

Architectural Plans of the Palazzo Riviera

Acknowledgements

FOREWORD

The Forbidden Book is based on facts. While the characters are imaginary and bear no relation to any living persons, the allusions to contemporary life are representative of early twenty-first century reality. Likewise, all mention of historical events and attributed quotations are authentic, translated when necessary by the Authors. The Afterword at the end of the book explains some items that may be of interest to readers, preferably after they have finished the novel.

ONE

“Look up, Leo. This is it,” said Professore Salvi.

They were inside the immense Basilica of San Petronio, in the heart of Bologna. Leo did as he was told, and rested his eyes on the fresco; as he was taking in the disturbing scene depicted, the professore spouted:

“His guts were hanging out between his legs;

“His heart gaped forth and that disgusting sack

“Which turns to shit whate’er one gobbles down.

“While I was all absorbed in seeing him,

“He stared at me and with both hands he wrenched

“His chest apart. ‘Look how I rip myself!

‘Look at how mangled is Mohammed here!

‘In front of me Ali treks weeping on,

‘His face slashed from his forelock to his chin.’

“And that’s exactly what the fresco describes. Does this sound familiar?”

Leo was embarrassed. His Italian colleague had recited the lines theatrically before a large congregation right before the beginning of Mass.

“Well?” Salvi insisted.

“Of course it’s familiar, it’s Dante,” Leo heard himself answer, in a hushed tone, “a scene from the Inferno.”

“A-ha!” commented Salvi; “and what about it?”

“I can’t believe this guy!” thought Leo as he replied, “It’s the 28th Canto. Dante and Virgil are in the ninth chasm of the eighth circle in hell; it’s the one of the Sowers of Discord, and the punishment there is to be mutilated. Mohammed shows his guts to the poets while on the left stands his son-in-law, Ali, his head split open.”

“Precisely,” said Salvi, smirking; “both were sowers of scandal and schism, and as such Dante punished them, and they’re burning in hell.”

“Shush!” said an elderly woman from a pew nearby, scowling at them.

“That’s our cue,” said Salvi, still loudly, “let’s get out of here.”

As they began to walk toward the exit, Leo said, in a whisper, “If you don’t mind, I was planning to attend Mass.”

“Really? What for?”

Leo didn’t reply.

After an awkward pause, Salvi resumed, “Well, suit yourself. But before it starts, let’s go have a quick espresso.”

Walking briskly, they crossed the piazza maggiore, and entered a busy café by the Fountain of Neptune.

“Two espressos,” barked Salvi, “and quickly, my colleague here has an appointment with God!”

The barista only imperceptibly raised his eyebrows and then busied himself behind the coffee machine. He dealt out saucers and spoons, adding their clatter to the babel of voices and the gory lines of Dante still echoing in Leo’s mind.

As Leo lifted his cup, a tremendous blas

t shook the café. The customers froze, met each other’s eyes and saw fear.

After a few very long seconds, the two professors rushed out to the square, where smoke, dust, flying trash, and an acrid smell assailed them. Wailing voices came from the direction of the Basilica. Leo groped forward through the swirling air.

“Stop,” cried Salvi, grabbing at his American colleague, “don’t go there!”

Leo shook himself free of the restraining hand. He reached the steps of the Basilica, but there was no portal: a cavern-like entrance gaped. The screams for help were clearer, and louder.

“You can’t do anything for them! Let’s go!”

But Leo went on. He slowly climbed the steps and peered into the church. Beams of sunlight burst through a newly rendered hole in the roof and made a bright column of the settling dust. All around were bodies, half smothered in fallen stone. Some were twitching feebly, like squashed insects. Others were struggling to their feet with groans, screams of pain, choking coughs. In the ray of sunlight, the same elderly woman knelt as in supplication, waving her arms. There were no hands on them, and beside her was a man with no head.

Leo was in a daze, his head spinning, his heart racing, his mind unwilling to grasp the enormity of what had happened. He must do something, but what?

He searched his pockets frantically for his rented cell phone and automatically punched 911. No reply. What in hell was the emergency number here?

To his left, only a few feet away, he saw an old man sprawled on the floor, blood gushing from his mouth. He knelt by him, holding his head with his hand. The man briefly looked at his rescuer, then his eyes closed. As Leo tried to revive him, a huge section of the roof caved in with a deafening crash, crushing yet more people beneath. Two fires were raging at the far end of the church.

Seconds passed, or minutes, Leo didn’t know, and finally police sirens began to wail and the first ambulances swerved into the piazza. The louder screeching of fire engines reached his ears. He remained on his knees, trying to comfort the dying man.

TWO

Two days later, the train to Verona was almost a phantom train, with hardly any passengers. After the massacre at the Basilica, Italians were staying home. Leo himself was haunted by what he had seen. If he had gone straight to Mass, instead of to the café with Professor Salvi, he might have been …

When he got off the train, the few people he saw had a vacant stare in their eyes. He made for the exit, blinking in the late spring sunshine. A man in a dark suit approached him. “Professore Kavenaugh? Professore?” he said in a heavy accent. This must be the Romanian butler Orsina had said would collect him. The man bowed: “Welcome to Verona; follow me, please.”

The butler hefted Leo’s bags and led him to a large car that looked entirely different from anything in America—a Lancia. Doubling as chauffeur, he ushered Leo into the back seat, then took the wheel. Soon they were out of the suburbs and in the countryside, with vistas over vineyards to right and left. After thirty minutes of raising clouds of dust as it raced along worryingly narrow roads, the car swept onto a graveled drive between high gateposts.

This was no mere villa, thought Leo as they ground to a halt before a columned portico, but a minor palace. Painted in the faded yellow color of polenta, grand and genteel, it gave him a feeling of ease. Once he met with Orsina and solved her problem, he was definitely going to enjoy his stay in such an idyllic place.

A bag in each hand, the butler led the way through airy frescoed halls, up a marble stairway, down a broad corridor, into a high-ceilinged corner bedroom. The view from the three large windows: a romantic garden to the left, with mature trees inviting walks beneath them; in front, rolling hills and vineyards, and the gravel road they had traveled on snaking through them. No other buildings in sight.

But where was Orsina? The butler had disappeared, so Leo ambled downstairs looking for someone, while taking in the frescoes of gods, giants, and heroes, the worn Persian rugs, the antique walnut furniture, and great Chinese vases filled with flowers.

Turning a corner, he almost bumped into a white-haired housekeeper who smelled, oddly, of vinegar.

“Buongiorno,” he said, and inquired about Orsina.

“La g’hè no la Baronessina,” she answered in what was presumably the local dialect. So, he was learning, Orsina was addressed as “Baroness.” More urgently, she was not there. Where was she? he asked. When was she expected? Marianna, the aged housekeeper, mumbled a few more sentences in her dialect, but Leo couldn’t understand them. Born Leonard Kavenaugh, of an Irish-American father and an Italian mother, he had learned Italian from the cradle, but never any dialect. He nodded intelligently to Marianna and walked out into the garden. The Romanian butler found him there. “Would the Professore like some refreshments?” Leo nodded and took the glass. “The Baron expects you before dinner for an aperitif at half past seven. Formal attire is requested.”

Leo gave in to the charm of a delicious pre-summer breeze in the shade of a walnut tree and, sitting on a teak bench, sipped his iced tea with peaches. The bombing in Bologna seemed light years away, and his mind turned to Orsina. Hired by Leo himself, she had been at Georgetown University a few years before, teaching Italian language and working on her own thesis. He had heard nothing from her since she left Washington. Then out of the blue had come a letter inviting him to spend some time with her in one of the family’s ancestral homes. Her uncle, she wrote, had given her an ancient book, supposedly of great importance but exceedingly hard to interpret. Would he help her to study and understand it?

Leo had accepted the invitation on impulse, and added a few days of research in Rome and Bologna. During the train journey he had tried to collect his memories of Orsina while wondering at his own decision. The trip had begun with catastrophe—or salvation. What else was he letting himself in for?

He went up to his room, to change and get ready to meet her uncle. The butler had unpacked his suitcase and left out what was evidently judged his best outfit. Leo had a distinct feeling of stepping back in time: a feeling both warm and disorienting, as if he had arrived in a novel set in Edwardian England.

When he came down, he found all the windows of the salone open to the cooling breeze. Baron Emanuele Riviera della Motta was sitting in an armchair, dressed in a mohair-and-silk suit of midnight blue that made Leo’s readymade wool blazer look inadequate, and too warm for the season. The Baron stood up. He was not tall but compact, and his sixty or so years had added no superfluous flesh to his frame. His white hair was swept back from a high, bronzed forehead. But what struck one most was the nose: a perfect Roman beak, crooked as an eagle’s.

“Professor Kavenaugh, I presume?” he asked. “How do you do?” and shook hands both firmly and formally. “Will you have a drink? I’m having bitter Campari. Would that suit?”

Leo had tasted it once and carefully avoided it since, yet he found himself saying “Perfectly, thank you.” When he sipped, it reminded him all over again of cough syrup on the rocks.

“My niece spoke highly of you,” the Baron said, staring at him appraisingly. For a moment, Leo felt as if he might add, “I wonder why?”

As the Baron occupied himself with his drink, Leo tried to make small talk. He mentioned the antique spinet in the corner, but the Baron cut him short, dismissing it with an English pun as “an instrument for spinsters.”

“And I have to sit through dinner with just him …” Leo said to himself.

“You’ve heard the news, I take it?” asked the Baron.

“The bombing in Bologna? I was in the Basilica minutes before the blast.”

“Really? Then you should be happy you’re alive! Dumitru, give the professor another Campari.”

“Oh no,” Leo thought as he smiled gratefully at the butler.

“A great tragedy,” added the Baron; “they’re now counting corpses. A difficult task, with some blown to smithereens, others charred beyond recognition, and some still under the rubble. The terorrists time

d the explosion well, right during the High Mass of Corpus Christi Day. You yourself have seen the huge congregation. All told, I wouldn’t be surprised if they counted hundreds and hundreds of dead.”

“My God, it’s so horrible!” exclaimed Leo. “But why? Who did it? Are there any suspects?”

“Who did it?” The Baron looked away from him, and concentrated on the frescoes on the ceiling. “You’ve heard of Giovanni da Modena, I take it?”

He had, from an Italian colleague of his, just two days before.

“That means you hadn’t heard of him before that? And you are the chair of the Italian Department at Georgetown University?”

Leo opted for another sip of Campari.

“I suppose he is not one of your major painters,” the Baron continued with exquisite condescendence, “but his frescoes in the Bolognini Chapel were brilliant. You see, Giovanni da Modena surpassed himself in the fresco of Mohammed and his son-in-law in hell. So, some Muslim guests of our country decided that this was an intolerable affront, and that the fresco was to be covered. Or, better yet, removed. Imagine that,” he said, raising his voice: “it’s as if you came to my home and told me that I must either cover or remove one of my frescoes!” The Baron was visibly angry. He continued, composing himself: “Some time ago, two Moroccans were overheard planning to bomb the fresco in the Basilica; they were arrested, then released, of course, though they had ties with Al Qaeda. Now it seems that Muslim terrorists have not only removed the fresco, but the entire Basilica with it, and the people inside it.”

“Is this conjecture on your part?” Leo finally asked.

“Yes, and no. To me it’s as obvious as a fact. Of course, it’ll take the carabinieri some time to reach this conclusion, and even more to prove it. Unless, of course, Al Qaeda or whatever group of Islamic terrorists speaks up and claims responsibility for the bombing. One way or the other, the ecumenical western world will soon have to come to grips with this reality.”

The Forbidden Book: A Novel

The Forbidden Book: A Novel